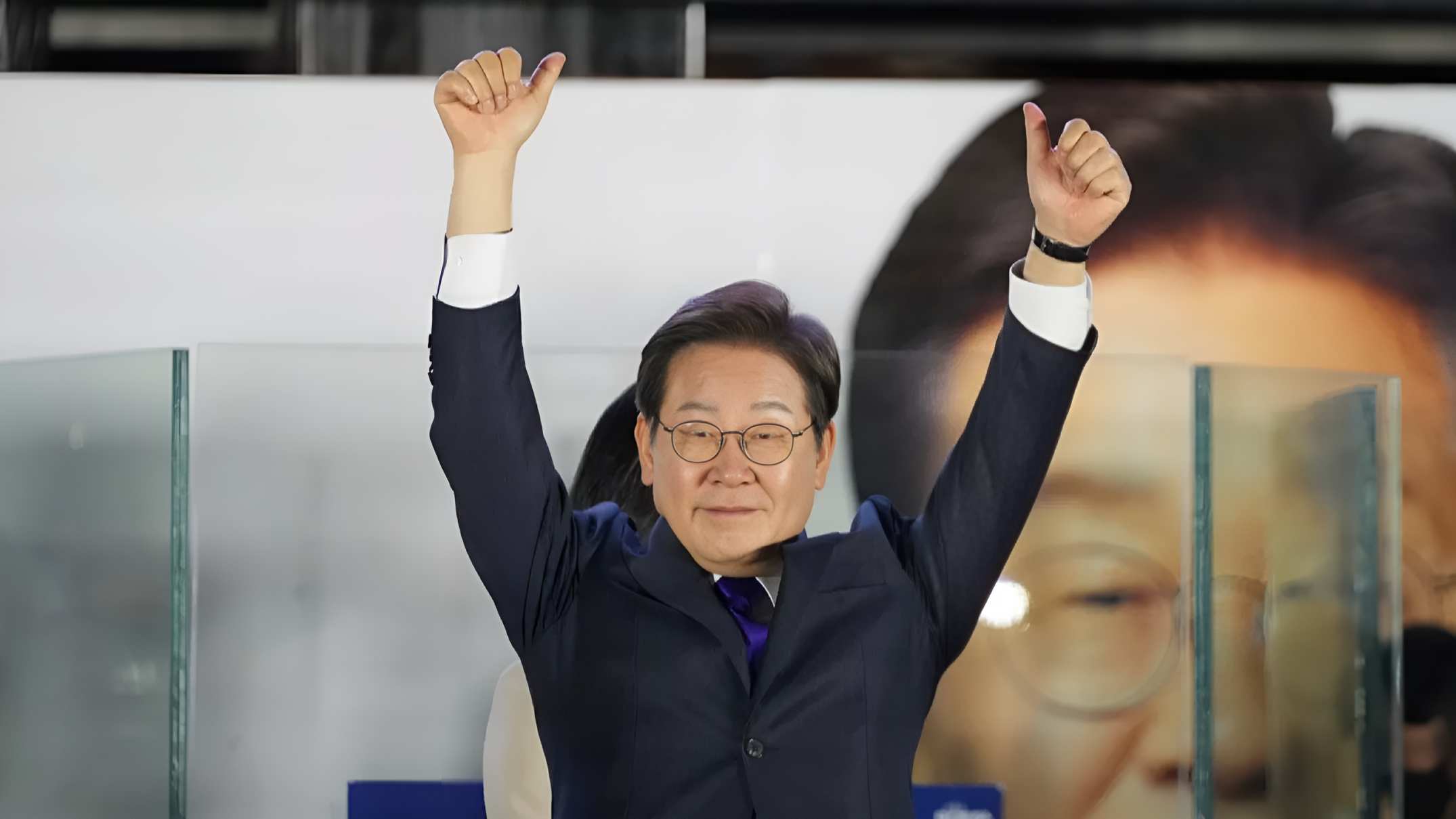

South Korea elects opposition’s Lee Jae-myung after political turmoil

Lee’s victory ends a period of intense political turmoil but sets the stage for new challenges, including uniting a deeply divided nation and managing complex foreign relations.

South Korea has elected opposition candidate Lee Jae-myung as president, six months after the previous administration’s failed martial law attempt triggered mass protests and led to the impeachment and removal of former president Yoon Suk Yeol.

Lee’s victory ends a period of intense political turmoil but sets the stage for new challenges, including uniting a deeply divided nation and managing complex foreign relations.

Lee, who narrowly lost to Yoon in a previous election three years ago, faced a fierce contest against ruling party candidate Kim Moon-soo, a former member of Yoon’s cabinet.

Early Wednesday, Kim conceded defeat, congratulating Lee on his win. Lee acknowledged the victory but focused on his first goal: "recovering" South Korea’s democracy.

The election came in the shadow of Yoon’s controversial martial law order, which sparked protests that ultimately ended his presidency and left the ruling People Power Party in disarray.

Two acting party presidents were impeached amid infighting, delaying their candidate selection. Analysts view Lee’s win as a rejection of the ruling party’s handling of the crisis rather than a strong endorsement of his policies.

Park Sung-min, president of Min Consulting, told the BBC, "Voters weren't necessarily expressing strong support for Lee's agenda; rather, they were responding to what they saw as a breakdown of democracy."

He added, "The election became a vehicle for expressing outrage… [and] was a clear rebuke of the ruling party, which had been complicit in or directly responsible for the martial law measures." According to Park, the vote showed South Koreans placed democracy above all else.

Despite the win, Lee faces major hurdles. He is due to stand trial on election law violation charges after the Supreme Court postponed the case until after the vote.

It remains unclear what will happen if he is found guilty, but current law generally protects sitting presidents from prosecution except for insurrection or treason.

Lee’s political career has been controversial, marked by scandals and an abrasive style that divided opinion.

He grew up in a working-class family, became a human rights lawyer, then entered politics, eventually rising to become the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate.

This time, Lee ran a more centrist campaign, promising to address issues like gender inequality.

The new president must also work with the fractured People Power Party, which still holds significant influence and support, especially among young men and elderly voters who remain loyal to Yoon and his right-wing narrative.

Many of Yoon’s supporters believe the martial law was justified and continue to claim election fraud, fueling protests and unrest.

Lee Jun Seok, another presidential contender who dropped out early, remains popular with young men for his anti-feminist views and could emerge as a key figure for Yoon’s base. This year’s voter turnout was 79.4 percent, the highest since 1997, partly driven by high participation among young men.

Beyond domestic issues, Lee will face urgent international challenges, including negotiating a trade deal with the United States under the Trump administration to counter economic pressures caused by tariffs.

The US remains South Korea’s key trading partner and security ally, making this relationship critical.

Lee promised to carry out his duties with full responsibility. “I will do my utmost to fulfil the great responsibility and mission entrusted to me, so as not to disappoint the expectations of our people,” he told reporters shortly after the results.